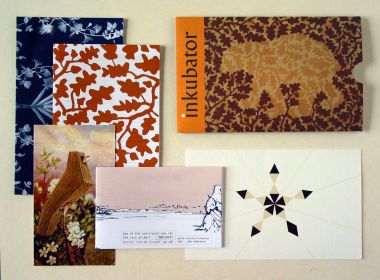

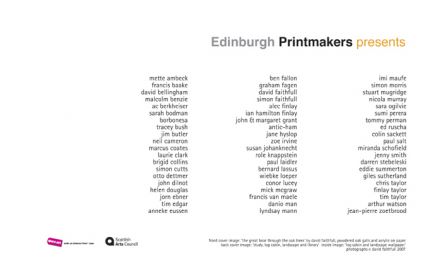

INKUBATOR

Gile Sutherland

‘Dort, wo man Bücher verbrennt, verbrennt man am Ende auch Menschen’

Heinrich Heine, 1820

As its title indicates, this exhibition and installation, conceived by the artist David Faithfull, is the second in the series of an ongoing, evolving project with coalesces around a collection of artists’ books, installation art and other aesthetic interventions.

An unusual, challenging and deeply stimulating project, it is, in essence, a conceptual framework which allows for the display of various media within a coherent and cohesive structure.

Faithfull himself has likened the project to an actual ‘multiple’ in that it is a kind artwork which is repeated, or has the capacity to be repeated, in almost infinite variation.

In Inkubator 1, shown at Edinburgh Printmakers in 2007, Faithfull divided the available gallery space into three conceptual and actual spaces, with a fourth, termed the Annexe, as an addendum with material which did not easily fit into any of the three other categories. These groupings, or rooms, labelled Study, Log Cabin and Landscape, housed a plethora of printed and visual material.

Faithfull sees the Study and the Landscape as antithetical spaces – where culture and nature oppose each other - with the Thoreau-esque cabin acting as a symbolic synthesis. Describing the concept, Faithfull has written:

'Study' or sanctuary for intellectual and scientific contemplation, political and philosophical speculation. 'Log cabin' or xylotheque where shaman meets poacher, twitcher meets stalker, a shrine or a retreat, a hide or a hideaway, an arboretum, the spiritual and the ritual, ecology and mythology, etc. 'Landscape' environment in flux, representations of topography, geology, meteorology, etc.,

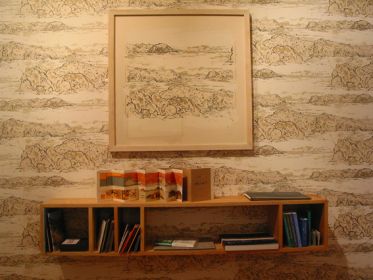

Within the Landscape are housed works on meteorology, geology and geography – as well as works on the landscape in art. Artists grouped within this area included Alec Finlay, Arthur Watson and Stuart Mugridge.

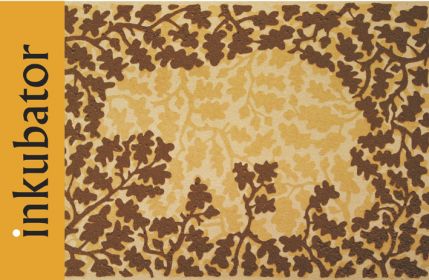

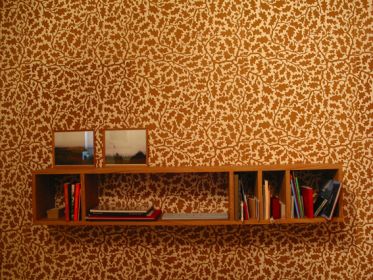

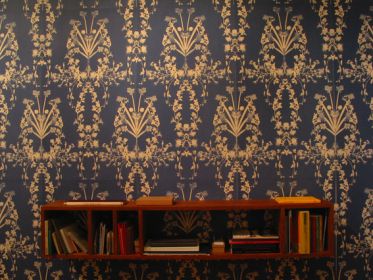

As part of his overall schema, Faithfull also conceived furniture (including shelving), wallpaper and other ‘decorative’ interventions. Thus, the Log Cabin contained printed hand-made wallpaper printed with an oak-leaf motif, a log bench, and a floor rug woven with a bear and oak-leaf design (itself a multiple woven in Iran). In the Study – which has a kind of Ruskinian ambience – we find a William Morris-inspired wallpaper by artist Nicola Murray derived not from Morris’s store of floral motifs but from a series of ‘mutated’ plants found in Murray’s allotment. These are complemented by comfortable floral pattern chairs, a putative ‘fireplace’ by Miranda Schofield (derived from the fireplace in one of Karl Marx’s former London homes) and a small, delicate writing desk.

The bookshelves – themselves another form of multiple – are fashioned from reclaimed mahogany from Dundee University’s Chemistry laboratories, in contrast to the Log Cabin’s locally sourced oak and the Landscape’s sustainable ash. In the Landscape, the walls are decorated by paper derived from Faithfull’s own landscape drawings (made from ink made by Faithfull from oak galls) while, in keeping with the outdoor theme, the furniture consists of deck chairs. Landscape drawings, thematically linked to the wallpaper, adorn the walls.

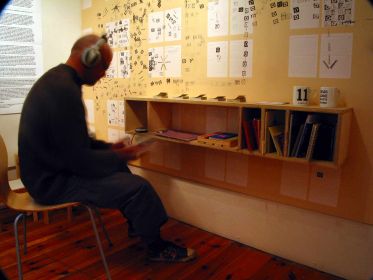

The Annexe, a repository of unclassifiable material, problematic material for any classification-addicted librarian, finds an appropriate taxonomy in this space, adorned with what appears to be astragalled window wallpaper in the fashion of the ‘seventies children’s TV programme, Playschool – is in fact an interactive wall diary by Chris Taylor and Craig Wood. This playful wall is complemented by a child’s work-table, also informing the viewers’ response and steam- bent, laminated plywood chairs. Here are filed the unclassifiable ‘picture books for grown-ups’ by Otto Dettmer as well as others, including, for instance, those relating to contemporary dance.

The context of Inkubator 2 has been determined by the physical space in which it has been displayed. Happenstance and circumstance have therefore dictated the evolving form. Faithfull, inventive, spontaneous and highly adaptive in his approach has allowed the Durham Art Gallery and Light Infantry Museum, with its obvious military context, to suggest themes of general conflict, Armageddon, the Cold War, apocalypse, nuclear weapons, Chernobyl and even related themes and images, such as the labyrinth of ancient legend.

Working with the Museum and Gallery’s Curator, James Lowther, Faithfull has sourced additional artists many of whom are based in the North East of England, to contribute to the evolving form of the Inkubator series. Most of these works are sited in a room Faithfull has labelled the Bunker. The space is purposefully and deliberately evocative of the themes suggested above. However, the work it contains also connotes personal as well as military national and international conflict and, as such, embraces a spectrum of dissent from the macrocosmic to the microcosmic. Conflict is thus, according to Faithfull, “an open premise”.[1]

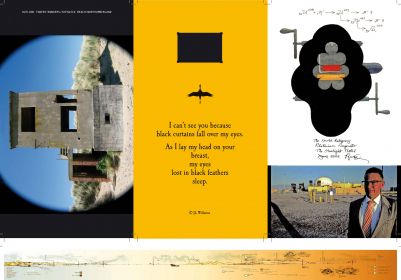

Within the Bunker, therefore, visitors can experience a series of atmospheric bunker photographs by Uta Kögelsberger. Printed on aluminium, these images portray the defunct, derelict concrete structures from the past conflict of the Second World War. Taken predominantly at night, or in the half-light of dawn or dusk, with long exposures, the photographs evoke the ghosts of the past inhabited by the eyes of the present. Kögelsberger has commented:

The bunkers and blockhouses from WWII could be described as being physical incorporations of terror. Their monumentality acts as a demonstration of the power of the state by inducing a fear and reverence that atomise the individual, inducing them into the service of an ideological whole. Their current gradual re-assimilation into the environment becomes metaphoric for the failure of these structures in their defensive role. [2]

Kögelsberger’s imagery is highly suggestive of the themes explored by the philosopher Paul Virilio, particularly in his work, Bunker Archaeology which, in the phenomenological vein of Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space, explores architectural space and place as an entity evocative of memory and emotion.

Faithfull, too, points to Virilio as a major influence on his thinking in respect of Inkubator 2:

Paul Virilio sees the bunker as a kind of ark for new life. But he also views it as a crypt, an old dank place which harbours the fear of being trapped and blasted by a grenade. The bunker, for Virilio, also contains the idea of resurrection. Once the nuclear dust has settled you come out of it like Lazarus, once the marauding army has gone. Virilio talks about Europe during the Second World War as being the first example in history of a ‘fortress without a ceiling’ where war came from above in the form of the allied bombings and Kosovo as a ‘fortress without walls’ with the advent of the graphite bomb, history progressing at the speed of its developing weapon systems[3]

Another of the ‘bunker’ artists is the ex-infantryman, Craig Ames. The artist who now works as a lecturer in photography the University of Sunderland comprises studies of infantrymen in what is now The Military Museum in Newcastle. Accompanying these are works by Stefan Gec from Gateshead whose work deals with Cold War and nuclear themes and those of Newcastle-born Gerald Laing whose images of the Iraq war, including the atrocities of Abu Ghraib prison, have won him acclaim and caused controversy in equal measure.

The sixth and final space of Inkubator 2, which Faithfull has labelled the Hangar, has been reserved solely for film and video works. These include films by Louise K Wilson, Angus Boulton, the Palestinian artist Leena Nammari and the collaborative artists Roland Rust and Volker Eckelmann whose work deals, respectively, with the absorption of Napoleonic ‘Martello’ towers into the suburban landscape and meditates on the route of the Docklands Light Railway, through Canary Wharf, in London.

There are, therefore, in each of these unique themed spaces multiple objects and texts which we may ponder at our leisure. They are by turns provocative, disturbing, intriguing, beautiful and puzzling.

One of the most absorbing of all if these, belying its apparent simplicity, is a small publication by the Berlin-based artist Wiebke Loeper. Loeper, brought up in the eastern sector of the city when the Cold War was at its height, was the privileged child of middle class intellectual parents. The family was allocated a flat in a newly built block of flats, the pride of the GDR’s economic and social programme. The book, entitled Moll 31 (indicating the address of the Loeper family’s apartment) is an outstanding exemplar of the artist book genre in terms of production, impact and execution. The cover, a vivid yellow, relates to the interior wall colour within the apartment when it was inhabited by the Loeper family. Interestingly the book’s epigraph is a quotation from Bachelard’s Poetics of Space – “ Das Haus ist unser erstes All. Es ist wirklich ein Kosmos”.

In Moll 31 Wiebke Loeper has juxtaposed photographs taken in the ’seventies by her father, architect Herwig Loeper – showing his beautiful blonde wife Bärbal Loeper and the couple’s children, inside and outside the utopian apartment – alongside those taken by the artist more than twenty years later. In one, Bärbal walks along the pavement with the apartment block in the background; the scale and perspective of both photographs are identical. With the passage to time, the trees have grown partially obscuring the block. The newer photograph is devoid of people and this theme defines the series – the unbridgeable gap between absence and presence, then and now. The images are an elegy for a lost childhood, a lost parent and a lost ideal – and are, in most cases, heartrending, even tragic. Another shows a bathroom with a child’s head, its hair covered in shampoo – a happy, family snap; its counterpart is a derelict abandoned space devoid of tiles, fittings – and child.

In the book the writer Annett Gröschner notes: “The history of the building reads like the history of the GDR which at the bad end of the metaphor scale was often compared to a house built on solid foundations. In the end the foundations proved to be faulty. By the summer of 1989, the building was already condemned…”

The apartment at Mollstrasse latterly looked like a bunker; and by extension we may view the GDR in the same light – a self-contained world, protected, enclosed and virtually impregnable which became redundant because of massive, external historical forces.

Elsewhere in this city of bunkers (from where so much of the apparatus of state terror, from the 1930s onwards, operated out of sight and out of mind) is another kind of bunker – a hole in the ground, into which one peers, not at things but at non-things, absences and ghosts. This is the architectural sculpture by the Israeli artist Micha Ullmann (b.1939), entitled ‘Bibliothek’ (1995). Sited in Bebelplatz near the Humboldt University and the [?] Library, the sculpture commemorates the burning of thousands of books by Nazi students on 10th May, 1933. The sculpture, simple in concept but deeply chilling, consists of a window down through which one looks upon empty shelves. That Ullman should have chosen to represent his vision as a subterranean space is telling; it evokes the notion of a bunker mentality in a city and a state which saw its ideals and apparatus as impregnable, to de defended to the hilt.

The adjacent plaque reads ‘Where books are burned in the end people will burn’. Heine’s prescience is as portentious as it is chilling. It serves as a warning to future generations and a reminder of Virilio’s view that our present nuclear technology cannot be truly understood and controlled until it is taken into the ‘ownership’ of artists, writers and intellectuals.

This exhibition represents one such part of this process.

GILES SUTHERLAND, August 2009

This essay is dedicated to the memory of Neil Manson Cameron (1962-2008)

[1] David Faithfull, Interviewed by Giles Sutherland, August 15, 2009

[2] Uta Kögelsberger, http://research.ncl.ac.uk/sacs/projects/Kogelsberger.html

[3] David Faithfull, Interviewed by Giles Sutherland, August 15, 2009

[4] The text reads: “For our house is our corner of the world. As has often been said, it is our first universe, a real cosmos in every sense of the word.” Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, p.

|

|